Street Address: Macdonald Park

It is perhaps surprising to learn that the city was once home to hundreds of cows.[1] In fact, the first year that animals were recorded in the city’s assessments, in 1838, more cows (157) were recorded than horses (151).[2] In striking contrast to the rich visual documentation of horses, cows were not readily documented in paintings and photographs of the city. Images one does find of cows (like the one below) often depict them outside the city looking in (much like standard contemporary representations of cows as belonging to the farms and fields of a sentimentalized rural landscape). In fact, Kingston’s cows lived all over the city. In the 19th and early 20th centuries one could find cows at the Orphan’s Home,[3] Kingston General Hospital, Morton’s Distillery,[4] the Dairy School,[5] the Markets,[6] and in many hotel and backyard sheds.[7] In the summertime, cows were pastured in land dedicated for that purpose. Macdonald Park, Caton’s Field, and Emma Martin Park were all at some point cow pastures.

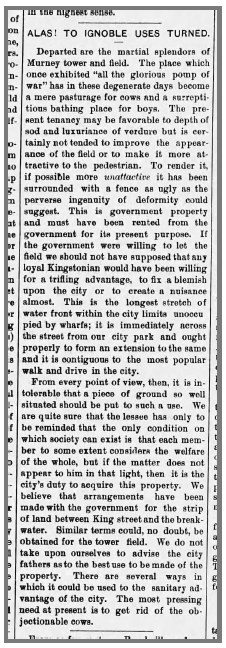

We are standing in Macdonald Park where annual meetings took place between the Mississaugas and the colonial authorities to mark the Crawford Purchase of 1783.[8] Initially intended for settlement, the Crown re-appropriated this plot of land in 1840 for military purposes, and constructed fortifications on it.[9] Despite Macdonald Park becoming a pasture as early as 1855[10] and cows being an important part of European colonization[11] very little attention has been paid to the many decades this area served as an urban animal space, primarily for cows. Nonetheless, newspaper articles show that by 1888 many Kingstonians felt the fenced land was a “blemish upon the city” and that such property could be put to better use, stating that “the most pressing need” was “to get rid of the objectionable cows.” [12]

While Kingstonians had many ideas about where they wanted cows to be, cows sometimes had their own ideas and would stray from their homes and pastures. Consequently, it was common for people to post “lost” and “found” adverts in Kingston’s newspapers. They would describe their cows in often intimate detail, such as Catherine McLachlan who in August 1841 put out an advert in the Chronicle and Gazette searching for a lost cow. While she did not name the cow, she described the cow’s body, noting that she was red with a black nose and nice horns. Another, unnamed resident, in May and June 1879 was looking for “a brown cow, with hind legs below the knee white, white star on forehead, and lower part of tail white.”[13] He went on to say that “anyone leaving information of her whereabouts at the Golden Lion Grocery will be liberally rewarded”. These details show how those who lived with cows knew them well and that there was something of an informal economy when it came to managing urban cows. A person who found a cow could charge the owner for the expense of looking after them but oftentimes they took cows to the city pounds.

In the same year the cow with a white star on her forehead went missing, the city created two more pounds – one in the south of the city (on Earl Street, near University Avenue), and another in the north of the city (near Patrick Street). The city had dedicated pound keepers, such as Samuel Shaw who looked after them. These pound keepers would get money from the fines people paid when collecting their cows, and if no one collected the animals they could be sold at auction or killed. The relatively ‘benign’ acceptance of cows’ wandering tendencies seemed to be coming to an end when in 1879, cows were increasingly described as “vagrants”[14] and “harassers”[15] who destroyed property and damaged lawns. This was reflective of changing property relations in the city whereby cows were increasingly understood as not only property themselves but as potentially damaging to the value of both public and private properties (including parks, homes, and streets). The same was true for Macdonald Park when in 1888 Kingstonians where increasingly irate that the land was being used for “objectionable cows.”[16]

Despite the changing tide regarding cows’ presence in the city, they remained within Kingston’s boundaries for many decades more. But today, other than their presence at the annual agricultural fair, cows are rarely (if ever) seen in Kingston as living beings (but they are omnipresent as milk, meat and leather). One can’t help but wonder which animals are ubiquitous in Kingston today who might become invisible in the city’s future. How can we better preserve and tell the histories and stories of the animals who make our cities what they are? How can we better appreciate the animals who are currently in and shaping Kingston today?

Notes and Credits:

Footnotes:

- [1] According to the City Assessments, between 1838 and 1879 Kingston was home to between 109-356 registered cows at any given point in time, meaning that thousands of cows have historically lived in Kingston (Queen’s University Archives, City Assessments).

- [2] 1838 City Assessments, Queen’s University Archives

- [3] Today this is the location of the John Deutsch University Centre. One of the few images of cows pictured in Kingston at this time is at the orphan’s home. One has to squint at the black to the right of the image and you will see a black outline of a cow (Queen’s University, V23-PuB-Orphan’s Home-1)

- [4] Morten’s Distillery is at what is today known as the Tett Centre. At one point in Kingston’s history, the distillery was home to hundreds of cows who appear to have been fattened up for slaughter using brewer’s mash (Cooper, 1856; The British Whig, 1844).

- [5] The Dairy School was formerly part of Queen’s University before the province took control of it. It was located at the corner of Clergy and Barrie Streets which is today a building for Public Health Ontario

- [6] Cows were sold as meat in the main market (what today continues to be Market Square) but they were also sold as live animals in the 2nd market which was located near the intersection of Place D’Armes and King Street East. The corner of Clarence and Wellington (in the very centre of the city) also became a “cattle ground” in 1843; it served as extra place for cows to stand near the market.

- [7] For example, in 1914 the Albin Hotel on Montreal Street was recorded has having two cows there (Queen’s University, Sanitary Inspector Property Inspections, 1914, book 4). But prior to the 1880s most cows in the city were kept as individuals in backyards with cow byres.

- [8] See the this stop in the Indigenous History Stones Tour.

- [9] Hatleid, L., 2006. MacDonald Park: A Cultural Heritage Overview. City of Kingston.

- [10] Office of Ordnance puts out an advert to lease the plot of ground today known as MacDonald Park, 26 July 1855, page 2, The Daily British Whig.

- [11] Anderson, V.D., 2004. Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.; Ficek, R. E. 2019. Cattle, Capital, Colonization: Tracking Creatures of the Anthropocene In and Out of Human Projects. Current Anthropology 60(S20): S260-271.; Fischer, J.R., 2015. Cattle Colonialism: An environmental history of the conquest of California and Hawai’i. UNC Press Books.

- [12] 27 July 1888, page 2, The Daily British Whig.

- [13] 31 May 1879, “Lost or Strayed, a Brown Cow.” The Kingston Daily News. Page 6. Accessed from Newspapers.com.

- [14] Reporting on City Council Proceedings, 10 April 1879, page 3, The British Whig.

- [15] 10 April 1879, page 1, The Kingston Daily News

- [16] 27 July 1888, “Alas! To Ignoble Uses Turned.” The Kingston Daily News. Page 2. Accessed from Newspapers.com.

Extras:

- The Cow with Eartag #1389 by Kathryn Gillespie

- Why we love dogs, eat pigs and wear cows by Melanie Joy

- Quick Cattle and Dying Wishes: People and their Animals in Early Modern England by Erica Fudge

- Oxen at the Intersection by pattrice jones

- Kill and Chill: Restructuring Canada’s Beef Commodity Chain by Ian MacLachlan

- Nutrition Policy in Canada, 1870-1939 by Aleck Samuel Ostry

- A Propensity to Protect: Butter, Margarine and the Rise of Urban Culture in Canada by W.H. Heick

- Animal City: The Domestication of America by Andrew A. Robichaud

- Cow, book by Hannah Velten

- The Cow: A Tribute by Werner Lampert

- The Geography of Livestock, a documentary by Atlaspro