Credits

Origins

The first Jews to arrive in Canada were sutlers—that is, pedlars who sold food and other supplies to soldiers—for the British forces in Quebec during the Seven Years War (1756-1763). Most eventually settled in Montreal and a Jewish congregation was established there in 1768.

It was not until Kingston became the capital of the United Province of Canada East and Canada West, from 1841 to 1844, that the city attracted its first Jewish resident, Abraham Nordheimer, from Bavaria. He was hired to be Governor-General Sir Charles Bagot’s music teacher. Within a few years, he left to join his brother in Toronto to manufacture pianos and help the Jewish congregation there procure its own graveyard.

The chevra kadisha, or burial society, is the first institution to be founded in nascent Jewish communities; ensuring proper burial usually precedes the building of synagogues. The date of the formal establishment of Kingston’s Jewish community, then, is 1897, the year Simon Oberndorffer, among others, succeeded in marshalling local efforts to purchase land for a cemetery on Sydenham Road, on the western outskirts of town.

Oberndorffer was also from Germany, arriving here in 1857 by way of New York. If German Jews such as the Nordheimers and the Oberndorffers constituted the first small wave of Jewish immigration to Kingston, the Eastern Europeans, or Ostjuden, comprised the second, and much larger, wave. To this day, their descendants comprise the majority of the Kingston’s Jewish population. Between 1891 and 1921, at a time when Jews were fleeing, virtually en masse, from the Russian Empire’s Pale of Settlement in the face of political chaos, pogroms, and economic liability, the number of Jews here grew from 39 to 303; that is, by a factor of eight. Meanwhile, Kingston’s overall population grew much more slowly in the same time period, from 19,263 persons to 21,753.

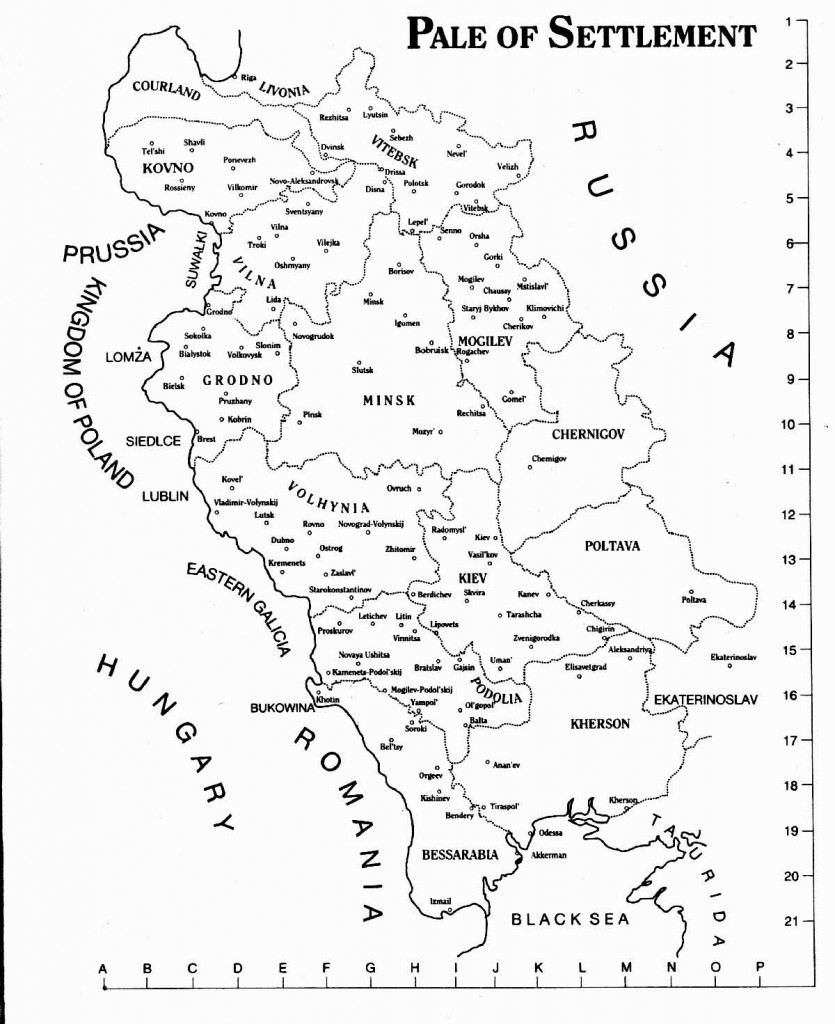

Czarina Catherine II promulgated the “Pale of Settlement” in the late eighteenth century as a means by which to delimit Jewish movement within the Russian Empire. It covered an enormous geographic area, including today’s Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Moldava, Ukraine (including the Crimea), and parts of Poland. The Ostjuden cannot, therefore, be lumped together as a single group; their local customs varied, as did their rites of worship. The nearer to Lithuania, the more likely they were to be strictly Orthodox; the further from it, the greater the likelihood of Hassidic influence. Though Eastern European Jews shared the same mother tongue, Yiddish, it was spoken differently in different places. There were at least three distinct forms: the central dialect (popularly referred to as “poylish/galitsyaner”); the northern dialect (popularly referred to as “litvish”); and the southern dialect (popularly referred to as volinyer/podolyer/besaraber”).

Most of the Ostjuden arriving in Kingston originated in the Russian Imperial gubernia or provinces of Grodno, Vilna, Kovno, and Vitebsk (i.e., modern-day eastern Poland, Belarus, Lithuania, and Latvia, in that order). A lesser number departed from Kiev and Podolia (northern and southern Ukraine), and still fewer from western and central Poland.

A Jewish settlement takes root when it acquires a cemetery. With the construction of a synagogue it begins to mature. In 1910, Kingston’s first synagogue (since demolished) was built on Queen Street, across from St. Paul’s Anglican Church. The project was made possible through the diplomacy and munificence of a recently arrived Eastern European immigrant, Isaac Cohen, originally of Lithuania. Thus Oberndorffer and Cohen, two businessmen—the former a cigar-maker, the second a scrap-dealer turned battery manufacturer—are often considered the founders of Kingston’s Jewish community.

Jewish Occupations

Almost all of the early Jewish immigrants, with the notable exceptions of Abraham Nordheimer and Simon Oberndorffer, dealt at first in second-hand and scrap goods such as clothing, furniture, metal and timber.

The reason was simple. Scavenging (what we now call recycling) was the most efficient mode of business for an immigrant group with little access to capital. Moreover, although a difficult way to make a living, the collection and resale of castoff articles and materials in one form or another afforded a measure of independence unavailable to the common labourer. For non-Christians living in a Christian land, self-reliance meant having the power to set one’s own hours and to observe one’s own Sabbath and holidays.

This economic pattern was not unique to Kingston or Canada. Novelist Mordecai Richler’s grandfather worked in a scrap-yard by the waterfront; so did Leonard Cohen’s. Ragmen scoured the streets of “The Main,” Montreal’s Jewish district, singing out “Rags, bones, bottles!” or “Old Clothes!” Even British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, though of a patrician background, was derisively referred to by his political opponents as “Old Clo’s”. In the United States, an incredible 90% of the scrap-dealerships were still Jewish-owned family businesses up until the 1990s.

The Jewish pedlar is as iconic an historical figure as the scrap-dealer; indeed the two occupations were inextricably entwined. As Gerald Tulchinsky writes in Canada’s Jews: A People’s Journey:

Many of these people began as pedlars selling merchandise from small carts or buggies in rural areas, or along the streets in towns and villages, securing the merchandise on credit from a metropolitan wholesaler. In a few years, he might have done well enough to open a small store. Instead of cash, some pedlars took livestock or produce as payment, while still others accepted any scrap metal, hides, or furs that farmers had for barter. Those seeking scrap metals, for example, sometimes offered new kitchen utensils to farmers in exchange for cast-off implements. Such metals would be hauled back to the pedlar’s yard, knocked apart with crow bars and sledge hammers, thrown into piles, and sold off to brokers who shipped it by rail or truck to the steel mills in Hamilton, Sydney, and Sault Ste. Marie. . . . These dealers served as commercial intermediaries between the nearby farms and the metropolitan centers. Pedlars and storekeepers offered much the same kind of link between the rural community and the growing populations in their towns, while, as purchasers from Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg wholesalers, they also linked the towns to the metropolises.

One man’s junk is another’s treasure. Bones were ground into meal for fertilizer; old clothing, if beyond repair, was processed into “shoddy” to make paper; and discarded furniture was broken down to make fuel, or refurbished as antiques. To this day, there are traces of the pioneering past in this city’s Jewish businesses. The giant KIMCO recycling plant on Counter Street began as a small scrap yard on Rideau Street. Kingstonians may be familiar with the Abramsky name, associating it with real estate; but the family business began a century ago with an ancestor’s stint as a pedlar at the corner of Princess and Division.

Big Cities versus Small Cities

As familiar as the patterns above may be to the student of North American Jewish history, comparisons between the experience of Jews in a city the size of Kingston and that of large urban centres reveal major differences—in terms of economics, religion, and settlement patterns.

Economically speaking, Kingston has not possessed the surplus population nor the infrastructure to sustain a large manufacturing base. Correspondingly, as Gerald Tulchinsky has pointed out, “here there was no Jewish working-class.” Despite their significant involvement in the clothing business as retailers, Kingston Jews never developed a garment industry along the lines and magnitude of those existing in New York, Montreal, and Toronto. For that reason, the kind of internecine labour strife those cities have known in the past, with Jewish manufacturers often pitted against Jewish workers, never found its equivalent here.

Similarly, the heavier the density of population, the more likely and vociferous intramural religious disputes are apt to be. Sizable metropolises usually boast at least four Jewish denominations—Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist Judaism—in addition to a range of Hasidic groups that could include the Lubavitcher, Satmar, and Bobover sects. These often compete with each other for the hearts and minds of Jewish citizens; they can also afford to be choosy about whom they allow into the fold.

By necessity, a more conciliatory spirit tends to prevail in smaller centres. Nominally Orthodox, while practically Conservative, Kingston’s Beth Israel congregation is illustrative of a spirit of cooperation and stability; begun as an amalgamation of three congregations, it will celebrate its centenary in 2010.

One noteworthy religious disagreement did occur, and brought about the establishment of a second congregation in Kingston, the Reform-affiliated Iyr Ha-Melech. This did not happen until the 1970s, however, an era which saw the hiring of a considerable number of out-of-town Jewish academics to teach at Queen’s University. This splintering off from the mother congregation Beth Israel, then, was less indicative of internal divisiveness than of the inability to accommodate a new demographic within the confines of the older, established congregational model.

The Jewish District/Residential Patterns

Before the Second World War, most Jews in Kingston lived where they worked. Their shops and homes were located predominately in the area of lower Princess Street and north of Princess towards Raglan Street, between Division to the west and Ontario to the east, hard by the waterfront.

Whereas the Jewish districts in places like New York and Montreal were often self-contained ethnic enclaves because of sheer critical mass, Kingston’s Jews, by virtue of their lack of numbers, were from the outset integrated more fully into the non-Jewish community.

In the Poland and the Pale of Settlement, Jews usually lived in shtetlach (little towns) segregated from their non-Jewish neighbors. When the mass migration of Jews to North America began in the late nineteenth century, it was not unusual for an entire shtetl to pick up and leave, only to transplant itself virtually intact in the New World. In Kingston, a smaller, family-scaled version of this phenomenon is detectable. As Steven Sloan wrote in his history of Beth Israel:

In most cases, the pattern of immigration followed along these lines: either the father or eldest son would emigrate, establish himself, and eventually send for the other members of his family. In Kingston, many residents adhered to this mode, among them Louis and Joseph Abramson, and their brothers-in-law J.B. Lesses and Isaac Zacks, who all came from an area in Russia known as Malch in 1895. Shortly thereafter came Keva Zacks, Isaac’s brother, and Saul Bennett, brother-in-law of the Zacks. Isaac Cohen came to form a partnership with Max Susman in 1898. Other established families were the Robinsons, Tevans and Turks. From Lithuania, sometime in the first decade of the twentieth century, came Meyer Rosen, who then sent for his father Moshe Velvel, his younger brother Hyman, and his sister Jennie. Joseph Abramsky first arrived in Kingston in 1893, because he had a friend, Max Teitelbaum, already living here. He returned to Poland, then came back to Canada for good in 1896, sending for his wife and children not much later. Abramsky also brought over three brother and a sister. . . . Benjamin and Ida Palmer both came from Grodno . . . in 1902-03. Ida’s uncle, Louis Langbort, was already here, as was her uncle Shimon Sugarman, who was Moe Sugarman’s grandfather.