Street Address: The foot of Brock Street

In many Indigenous traditions, salmon are recognized as forming their own “people” or “nation” with a distinctive role to play in creation, and as such are frequently portrayed in Indigenous art and stories. In Anishinaabe teachings, for example, fish (Giigoonh) are believed to be holders of the stars and of wisdom.[1]

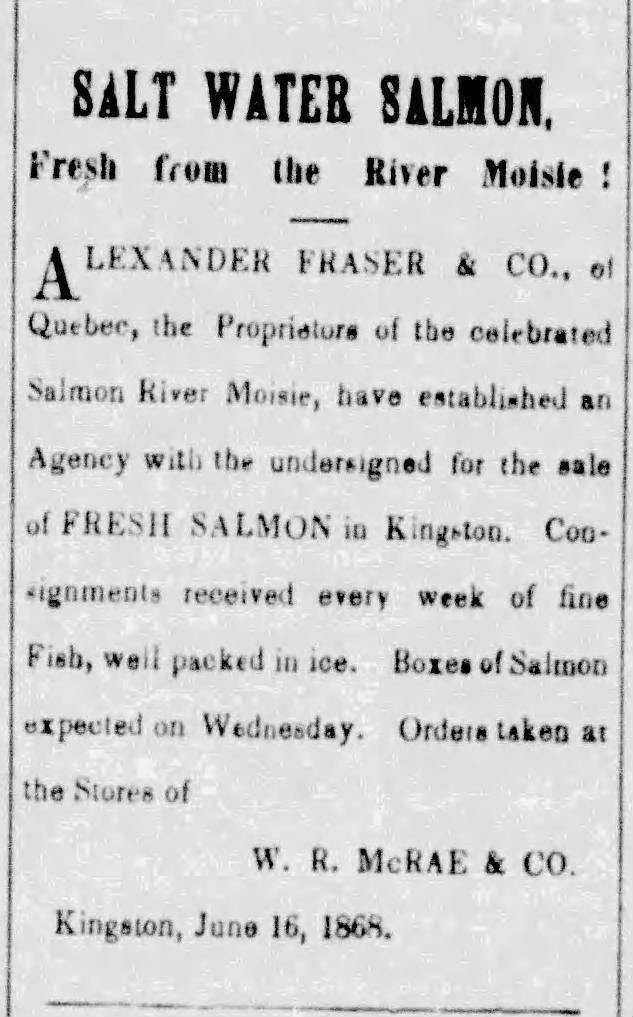

Salmon were a vital food source for Haudenosaunee peoples who used to fish for Kontihnawa:ra in Lake Ontario between September to November.[2] At the end of the American Revolution when colonial settlement along the shores of the Lake intensified, salmon became an important food for settlers, too, who often traded with Indigenous fishers in the Kingston region. “The appeal of salmon to potential frontier settlers was great: it was a food that would come to them in their new homes under its own power, it could be captured relatively easily and safely, it was more reliable than the charity of their fellows.”[3] Consequently, salmon became a vital component of settler diets, eaten fresh, when possible, with the remainder salted for the winter.

In 1846, Kingston’s fish market was located at the foot of Brock Street. Edwin Horsey (1934: 66) in his book chronicling life in Kingston at that time says that “fishing boats landed and were drawn on the shores in rows, and the fish exposed for sale (before the fish house was built).”[4] At the time, Atlantic Salmon would still have been sold at market, but they were a rapidly declining part of the Lake Ontario ecosystem. In earlier centuries reports about the ubiquity of Atlantic Salmon were common. The animals spawned in the gravel beds of various streams and rivers that flow into Lake Ontario, including several in and around Kingston. Around age three, the fish would leave the streams for the open lake, mingling with other salmon before returning upstream to spawn. Unlike their Pacific counterparts, these salmon can spawn more than once in their lives.[5]

This increasing consumption of salmon coupled with disturbances to their habitats made by pollutants from mills and factories on shore, the removal of trees, the erection of canals, and rapid urbanisation saw their numbers plummet until in 1898 it is believed the last Lake Ontario Atlantic Salmon was caught. The species had suffered what is known as a local extinction (or extirpation). Some of their Pacific kin (known as Chinook and Coho) were introduced to Lake Ontario in the 1860s, but unlike the Atlantic Salmon, these fish only spawn once and are not indigenous to the region. In 2006, a program was launched to try to reintroduce Atlantic Salmon. It is colloquially known as the “Bring Back the Salmon Restoration Program” and is supported by the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters. Atlantic Salmon are now spawning in the Credit River, near Niagara, after being absent for 150 years.[6] It is interesting to think about the connections between hunting, conservation, and colonialism. What does it mean to introduce or even reintroduce a species so that they may be hunted again? How do these removals and additions change animal “nations” and their ecosystems?

Notes and Credits:

Footnotes:

- [1] Anishinaabe teachings fish (Giigoonh), available from saultribe.com.

- [2] Kuhnlein, H.V. and Humphries, M.M., n.d. “Traditional Animal Foods of Indigenous Peoples of North America: Salmon.”

- [3] Tiro, K.M., 2016. A Sorry Tale: Natives, Settlers, and the Salmon of Lake Ontario, 1780-1900. The Historical Journal, 59(4): 1001-1025.

- [4] Horsey, E., 1934. Kingston: Cataraqui, Fort Frontenac, Kingston. It was only one of the markets where animals were historically bought and sold in Kingston. Animals were also sold at the main market at Market Square and the Hay Market near Place D’Armes

- [5] Tiro, K.M., 2016. A Sorry Tale: Natives, Settlers, and the Salmon of Lake Ontario, 1780-1900. The Historical Journal, 59(4): 1001-1025.

- [6] Nature Conservancy Canada, 2016. “Atlantic Salmon: Lake Ontario’s Ghost Fish”

Extras:

- What a Fish Knows: The Inner Lives of our underwater cousins by Jonathan Balcombe

- To Sea & Back: The Heroic Life of the Atlantic Salmon, by Richard Shelton

- The Atlantic Salmon in the History of North America by R.W. Dunfield.

- Salmon, by Peter Coates

- Atlantic Salmon: An illustrated natural history by Roderick Sutterby and Dr. Malcom Greenhalgh

- First fish, first people: Salmon tales of the North Pacific Rim edited by Judith Roche and Med McHutchison

- Keystone Nations: Indigenous Peoples and Salmon Across the North Pacific by Benedict J. Colombi and James Brooks

- Salmon: A Fish, the Earth, and the History of a Common Fate by Mark Kurlansky.

- A Sorry Tale: Natives, Settlers, and the Salmon of Lake Ontario, 1780-1900 an academic article by Karim M. Tiro.

- The role of fishing in the Iroquois Economy, 1600-1792, an academic article by Michael Recht.

- The history of the Atlantic Salmon in Lake Ontario, an academic article by John R. Drymond, High H. MacKay, and Mary E. Burridge.

- Chronology of Lake Ontario ecosystem and fisheries, academic article by Brian P. Morrison.

- The Atlantic Salmon an oral history by Gary Pritchard/The Golden Eagle

- Salmon in Toronto and GTA Waters a web page by the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority

- The Lake Ontario Atlantic Salmon Restoration Program, a webpage by Bring Back the Salmon