Street Address: 251 Ontario Street Canada, The old Fire Station

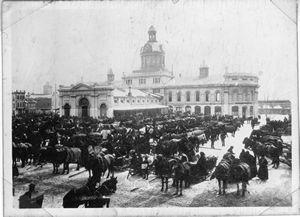

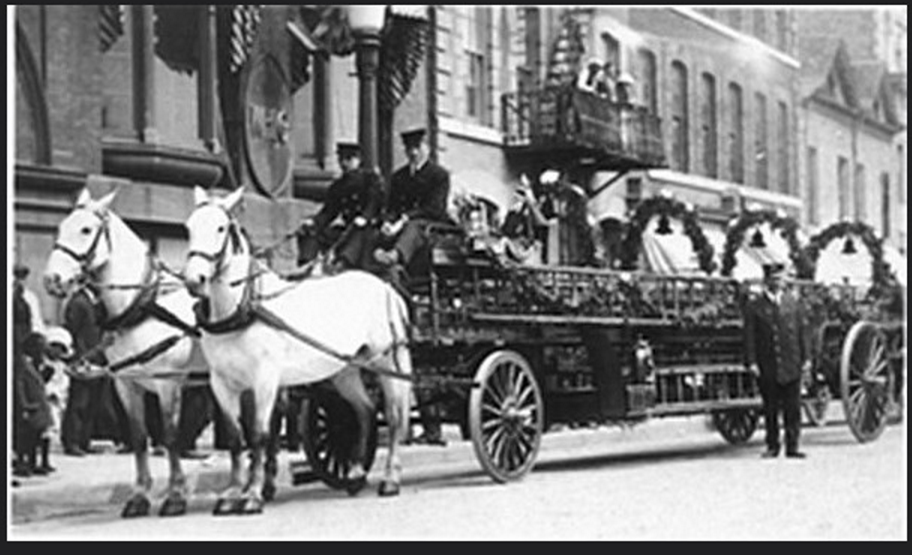

Perhaps few animals inhabit the urban historical imagination more than horses. From Western films where horses dominate the streets of frontier towns to period dramas showing them at work on the busy thoroughfares of London, horses have long and varied histories in towns and cities. The same is true for Kingston. Today you might see an occasional horse mounted by a police officer on Princess Street, or harnessed for a carriage ride at Market Square, but historically Kingston was home to hundreds of horses used for transport and power. As the human population in Kingston grew, horse populations increased and the jobs they were expected to do became progressively more varied. There were 151 horses recorded in Kingston in 1838[1] and this figure jumped to 788 by 1893.[2] Horses were tasked with conveying people, pulling carriages, hauling ice, assisting garbage collectors, and powering streetcars.[3] One of their most skilled jobs was working as fire engines, helping firemen like William Lemmon who worked and lived at the fire station located at what is today Lone Star restaurant. [4] These horses were essential to bringing the necessary water to battle fires across the city.

There were, however, some concerns about how horses were treated in Kingston and their prominence in the city contributed to the establishment of the 1848 Bill to Prevent Cruelty to Animals, most of which focused on ensuring that animals like horses were not worked “excessively” or treated “inhumanely.” [5] The Humane Society would become an important organization addressing cruelty against animals in the city. The Society would often issue warnings and fines as well as write letters to newspapers about what they thought was inappropriate treatment of animals. [6]

Despite the Bill and the existence of the Humane Society, urban horses continued to face many challenges in Kingston. They got stuck in muddy streets, were made to race, fell through ice, and worked in grueling conditions. For example, on the 22nd of March 1884 a horse dropped dead on Ontario Street after running into the end of another cart, and in 1893 during a race in the harbour a horse was injured and passed out from overexertion.[7] Many residents of Kingston also worried that the arrival of cars would harm and scare horses and they were not wrong. Spooked and frustrated animals ran down streets and, in their panic, hurt themselves or others – such as a horse owned by “Gypsy” Taylor who is 1897 slipped and broke his hind leg after being driven off the road by a buggy.[8] While cars often frightened horses, they were also the key technological advancement that caused a rapid decline in urban horse populations in Canadian cities. Cars could now be used to carry garbage, attend to fires, and transport people, and they didn’t rebel at being subjected to human control. The shift from horses to cars is a reminder of how quickly and dramatically power and transport infrastructure can change and the significant implications this has had for how both humans and horses live their lives.

Notes and Credits:

Footnotes:

- The number of horses recorded in the City Assessments for 1838. It is likely that there were more horses than what are recorded in these tax documents as they likely did not include young horses (1838 City Assessments, Queen’s University Archives).

- This is according to the City Assessments for that year (Queen’s University Archive) but in a Historic Kingston piece with newspaper extracts from that year the Assessor is said to have recorded 821 horses (Anon. 1993. “Kingston Day by Day – 1893,” Historic Kington, 41: 75-121). I chose the lower number so that there was constituency across documents but again, it is likely that there were more horses than what was recorded in the assessments.

- A striking visual trace of Kingston’s vanished horse community is the abundance of arched limestone carriageways and carriage houses dotting Sydenham ward.

- William Lemmon suffered an injury in 1883 when he fell off his horse who then stepped on and broke his jaw. 1883-08-23, “Stamped upon by a horse,” The Daily British Whig. Page 3.

- 23 December 1848, “Bill: An Act to prevent cruelty to animals,” British Whig. Page 3.

- 1 June 1888, “Kingston Humane Society,” The Kingston-Whig Standard. Page 5. 18 January 1890, “Let the Humane Society,” The Daily British Whig. Page 2.

- Importantly, urban horse deaths such as these still happen in cities today. In October 2022, Ryder, a horse-carriage horse in New York City died as a result of over-exertion and this has sparked renewed debate about the place of such horse carriages in the city.

- 4 June 1897, “Killing of a Horse,” The Daily British Whig. Page 6.

Extras:

- Horse, by Elaine Walker

- The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century by Clay McShane, Joel Tarr, Professor Joel Tarr

- From Horse Power to Horsepower: Toronto: 1890-1930 by Mike Filey

- The Horse in Human History by Pita Kelekna

- Animal Metropolis: Histories of Human-Animal Relations in Urban Canada, Edited by Joanna Dean, Darcy Ingram, and Christabelle Sethna

- A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement by Ernest Freeberg

- Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Swart

- Governing Animals: Animal Welfare and the Liberal State, academic article by Kimberly K. Smith

- The Evolution of Horses, a webpage by the American Museum of Natural History

- Gentrification Is Erasing Philly’s Black Horse Stables, a mini documentary by VICE

- The Evolution of Horses, a podcast episode by In Our Time