Credits

Introduction

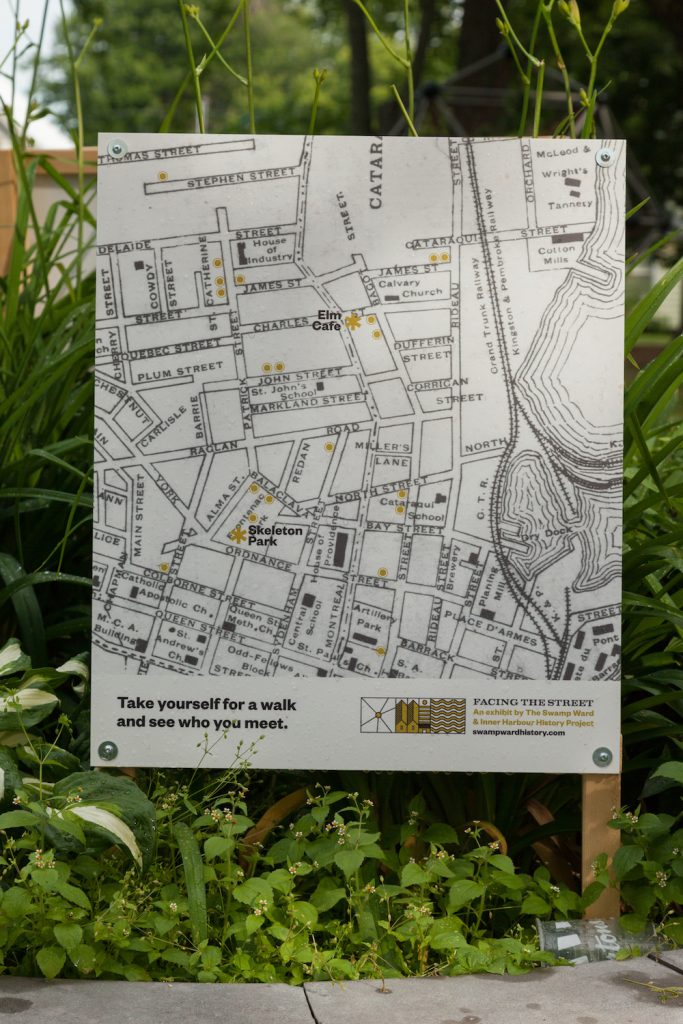

In June 2018, with funding from the City of Kingston Heritage Fund, Laura Murray and Chris Miner curated a photography exhibit titled Facing the Street. This exhibit shared family photographs belonging to people interviewed as part of the Swamp Ward and Inner Harbour History Project (SWIHHP), directed by Laura Murray. Some photographs appeared in public spaces where they were taken — that is, in their geographical context — and others were exhibited with a bit more historical context in the Elm Café. As a way of making part of that exhibit available more permanently, and of contributing to the Stones website, Swamp Ward Snapshots was developed to share a selection of photographs and associated information.

Some of the images in Swamp Ward Snapshots were featured in Facing the Street, and some were not; also included are some photographs of people who gave us photographs and people who looked at them. Interaction between strangers, between generations, and between newcomers and “old-timers” was a key goal of Facing the Street. We may not be friends with all our neighbours, but in recognizing each other at least enough to smile or say hello, we create community. We can think of the same phenomenon across time. After all, the land beneath us, the houses we live in, and the streets we walk on, were home to others before us. And they will be home to others after us. Most of these people we will never know, but they too are our neighbours.

It should be acknowledged that “Swamp Ward Snapshots” only represents a few people. Those who lived here before the advent of photographs, who were not photographed, whose families left, whose descendants did not keep their photographs, who felt uncomfortable going public, who didn’t get around to getting back to us (!), or who simply have not come to our knowledge — you aren’t going to see them or their families. We also limited Facing the Street and thus Swamp Ward Snapshots to black and white photos at least sixty years old. But we hope that in seeing a few striking faces, you will be prompted to imagine and honour — or maybe research! — others as well.

The people missing from the photos include the photographers. We do not know the names of most of the people who took the photos featured here. But these are very artful images — indeed, not just “snapshots,” despite our title. And as they are art, they are also artifact. In scanning, we have been careful to preserve signs of repeated viewing, mounting, and care. It is not only the originators of artifacts who are important, after all, but those who keep them, remember what they are, and share them.

The Swamp Ward

It may be helpful at the outset to gloss the term “Swamp Ward,” since it does not appear on any map. It is not an official term. Rather, it seems to have arisen as a pejorative nickname for the Cataraqui Ward, a former electoral district in the City of Kingston. Though it doubtless arose earlier, the term appears in a 1871 letter to the editor of the Kingston News, and the British Whig in 1884 reported that “the Mashers of swamp ward” won a baseball game over the “Dudes” of Ontario Street.

The Cataraqui Ward, which ran up the west side of the Cataraqui River, was definitely swampy. Wetlands made for good fishing and hunting for Indigenous residents, and the word Ka’tarohkwi means “marshy wet place” in Huron language. White settlers had little use for such environments. Although the tannery was built in marshlands so water could carry away effluent, most industries sought — and created — firm divides between firm land and water. Kingston’s Inner Harbour — now Douglas Fluhrer Park — is made of cinder and other fill from the railroads. Other swamps, and indeed the entire marsh between Belle Island and the mainland, were filled in with garbage. Stuart Crawford remembers the big oil tanks where Rideaucrest Home is now leaking into swampy areas below, providing opportunities for children to make torches out of cattails, with exciting results. Mike Tureski remembers how, skating on a pond north of James Street around Bagot, the ice was soft and you could end up having your skate sink into “gunky tar” dumped there from the coal gas plant on Barrack Street. So you can see that the term “Swamp Ward” ended up referring not only to swamps, but to the industrial uses and indeed the workers associated with them. Outsiders used it as a term of insult, but insofar as workers and their families thought of this area as home, to them it was a term of pride. After the industries shut down in the 1960s and 70s, people who had the means started leaving the area for the suburbs, and some who stayed felt shame and stigma. At this point, the term “Swamp Ward” fell out of use or was considered derogatory. It was generally replaced by a broader term, “North of Princess.” In recent times, the name “Swamp Ward” has been reclaimed by undertakings such as the 1980s Swamp Ward Festival at St. Paul’s Church, and the Swamp Ward and Inner Harbour History Project. Now, ironically given its former stigma, the term is used by real estate agents. Overall we can see that the fortunes of the name follow the fortunes of the part of town it refers to.

For more information, listen to the podcast What’s in Name?, or see maps on the SWIHHP website.

The Swamp Ward and Inner Harbour History Project (SWIHHP)

SWIHHP was initiated in 2015 by Queen’s University Professor Laura Murray and she continues to develop its directions and events. It defines “Swamp Ward” broadly to include the area of Kingston from Division Street to the river, from Queen Street to Stephen Street. The entire SWIHHP oral history collection of almost one hundred interviews along with photographs and other research materials will be donated to the Queen’s University Archives. In the mean time, for over fifty short essays concerning the area and its people, as well as links to seven podcasts, see the project website.