Street Address : 137 Queen Street

Period : 1750-1800

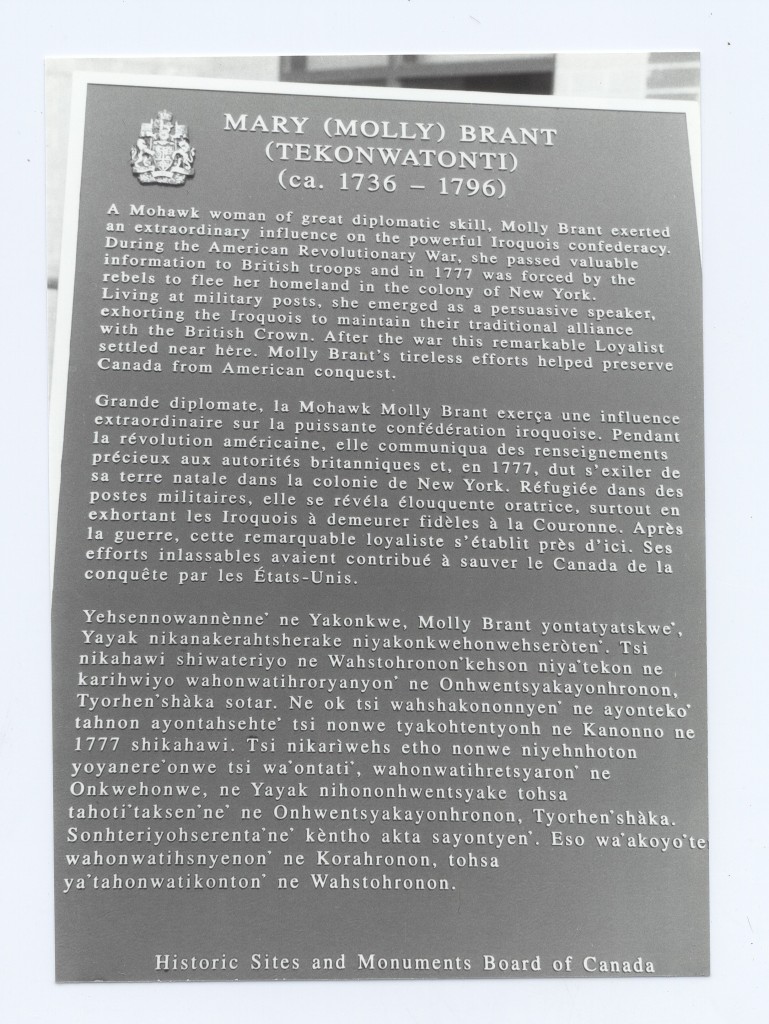

Molly Brant, otherwise known as Degonwadonti (meaning “many opposed to one” in Mohawk), was the sister of Joseph Brant. She played a crucial role for the Mohawk during the American Revolutionary War and was instrumental in the prosperity and enduring heritage of Cataraqui.

Molly and her brother Joseph grew up in the home of their mother and step-father, Nickus Brant. The identity of their biological father is debatable, as in Iroquois tradition surnames are matrilineal. Within Iroquois nations, clan mothers hold decision making power. The clan mothers are responsible for governing and tending to the primary food source (agricultural produce; with men’s hunting being a supplementary source), electing chiefs and voting in any economical or political affairs that arise. Molly Brant was to become clan mother, and so she was trained in Haudenosaunee tradition. She often accompanied elders on political and business trips to Europe and became well educated in both European and Indigenous affairs. This made her an ideal representative not only for her Colonial community, but for her Haudenosaunee community especially.

In approximately 1759, Molly married the British superintendent of Indian Affairs (and close friend of her step-father) Sir William Johnson. She lived with him in Johnson Hall in New York from 1763-1774, where she was referred to as “housekeeper”, as the Church of England refused to recognize their marriage (as they were married in the longhouse). It is said that Molly’s “sparkling black eyes” and long, braided black hair is what captured Johnson’s attention. Johnson was, however, involved with another woman simultaneously: Catherine Weissenberg, a German woman who worked for him and the mother of his first three children. Weissenberg died in 1759, the same year Molly gave birth to her first of eight children (who survived past infancy) that she bore Johnson. At the time, fathering children with multiple women was acceptable, especially if they could be provided for.

Although Molly was alluded to as “housekeeper”, she was known to accomplish few, if any, housekeeping duties, but rather she assumed responsibility for organizing the various social activities that took place at Johnson Hall. She was a gracious host who welcomed all. Judge Thomas Jones describes the atmosphere in the house as open and free:

“After breakfast, while Sir William was about his business, his guests entertained themselves as they pleased. Some rode out, some went out with guns, some with fishing-tackle, some sauntered about the town, some played cards, some backgammon, some billiards, some pennies, and some even at nine-pins. Thus was each day spent until the hour of four, when the bell punctually rang for dinner, and all assembled. He had besides his own family, seldom less than ten, sometimes thirty. All were welcome. All sat down together. All was good cheer, mirth, and festivity. …? Each guest chose what he liked, and drank as he pleased. The company, or at least a part of them, seldom broke up before three in the morning. Every one, however, Sir William included, retired when he pleased. There was no restraint. ”

Molly’s amicable disposition and sincere acceptance of all who visited Johnson Hall led her to a position of prominence and influence among the Mohawk people. Her lifestyle at Johnson Hall was far from what white settlers perceived as the “inferior” Native way of life. In fact, Molly acted more like clan mother in the household, attending to political and economic affairs, as well as stepping in to help with the daily affairs of the Indian Department when Johnson was away.

After Sir William Johnson died in 1774, Molly, along with her children and other Loyalists, eventually fled from New York to Canada; first residing on Carleton Island, then in Cataraqui in a home that was built for her (in recognition of her leadership and unwavering loyalty to the British). Though Molly was immersed in European culture, she adamantly insisted on dressing in customary Haudenosaunee apparel and remaining connected to her heritage. The post-Revolution period saw a strict segregation between Haudenosaunee and European ethnicities in Cataraqui: at times the Mohawks, women especially, were mocked and belittled for their traditional Native dress, which generally consisted of lace-up shirts, leggings and moccasins. Molly’s cultural pride and dedication to tradition remained intact, however her brother, Joseph Brant, encouraged acculturation to the surrounding European fashion, both literally and figuratively, among his people. Molly’s strong desire to resist acculturation is understandable: Mohawk women had both economic and political power to lose with the departure from a role such as clan mother, which was both acknowledged and influential among the Mohawks.

Molly and Johnson’s daughters, all of whom married into high society (their husbands being respected, well known doctors and captains) followed Joseph Brant’s lead and assumed the mannerisms and dress of their European peers. One incident in particular amplified their desire for conversion: when out in public one day in their Haudenosaunee dress, they were verbally assaulted with derogatory remarks and innuendo by a group of young European army officers. Later that evening, they encountered the same men at a formal event, dressed in elegant ballgowns. The men apologized for their earlier behaviour and asked them to dance, in an attempt at redemption. The sisters, however, refused and left, still feeling humiliated and upset. This encounter alone is evidence of the disconnect between the two cultures. While it was perhaps not the first choice of Mohawk women to assimilate to the culture of another, it was one of the only ways they could be viewed as educated and of higher social status in a society where European culture dominated.

Molly Brant, on the other hand, found a way to thrive while living between the two cultures. She remained loyal to her Mohawk heritage, yet earned the respect and recognition of her European community as well. She was a leader and a constant source of support, affirmation and encouragement for Mohawks and Europeans alike. Though the trials of her life speak to the broader difficulties faced by Aboriginal Peoples in the past – and perhaps still to an extent in the present – she played a crucial role in the endurance and progression of her people and paved the way for others to follow in her footsteps, until her death in 1807.

*See also Reverend John Stuart (St. George’s Cathedral), William/Johnson Streets, Earl Street

Return to Indigenous History Map