Period : After 1950

The Queen’s Homophile Association (QHA) was established in 1973 to provide a supportive space for lesbians and gays at the university and to counter negative stereotypes of homosexuality. The university’s queer organization, under various names and guises, has historically been housed in the Grey House, and the presence of a public organization in a small city like Kingston has been significant both on a political and an individual level, increasing visibility for gays and providing a forum for friendship, support, and self-acceptance.

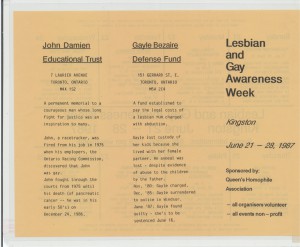

Although the early 1970s saw an explosion of gay rights organizing, from the outset the QHA was not intended to be a political organization. While contemporary groups such as the Community Homophile Association of Toronto (CHAT) and GO (Gays of Ottawa) were implementing a legislative human rights strategy, the primary focus of the QHA was to educate its members and the community so that gays, lesbians and bisexuals felt safe to “come out”. On the other hand, the QHA did engage with gay rights activism by welcoming George Hislop, a prominent gay activist and founder of CHAT, as a speaker at Queen’s; by holding a fundraiser for John Damien’s legal fees after he was fired in 1975 from his job at the Ontario Racing Commission “because he’s a homosexual”; by sponsoring a national conference in 1976; and by participating in various national networks.

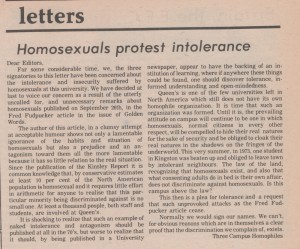

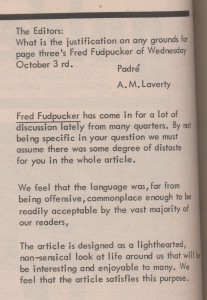

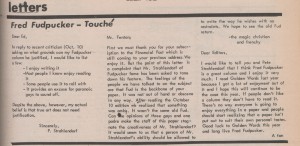

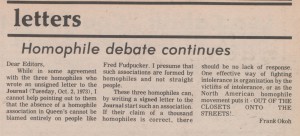

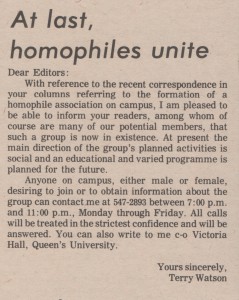

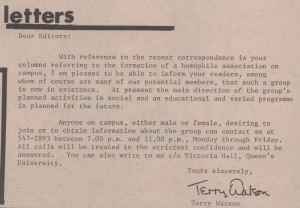

Setting in motion a chain of events that would lead to the Homophile Association’s inception, on October 2, 1973 a letter signed by “Three Campus Homophiles” appeared in the Queen’s Journal in response to an anti-gay letter titled “Fred Fudpucker” published in the engineering paper, Golden Words. The homophiles voiced their concerns about the homophobic attitudes on campus, which included incidents of physical violence and intimidation, and pointed out that “Queen’s is one of the few universities left in North America which still does not have its own homophile association.” The following weeks saw a flurry of letters representing a range of views on the matter. Although public response was generally in favour of homosexuals starting their own organization, opinions published in the Queen’s Journal dismissed and belittled the “three homophiles” and their feelings of alienation, refusing to acknowledge that Queen’s was a hostile environment for gays. Nevertheless, by the end of October 1973, the homophile group was official. Announced first by a letter to the editor and followed by a Journal news story, the group encouraged people interested in joining to write c/o Terry Watson at Victoria Hall or to call the Gay Rap Line 7 p.m.-11 p.m., Monday to Friday. “Terry Watson” was a pseudonym available for use by anyone in the group, male or female. Organizers purposely selected a sexually ambiguous name in order to appear open to both men and women and to show that the QHA was not a sexist organization.

Nevertheless, significant gender divisions were present from the group’s inception. Maureen remembers calling the Gay Rap Line for Terry Watson and having the man who answered believe that she was making a joke because “it had completely escaped his thought that there were women homosexuals out there who might be interested.” Maureen also notes that she ended up dividing her time between the QHA and the Kingston Women’s Centre because “the guys wanted women at their parties so that no one would know they were gay, but we were budding feminists and we didn’t want to be the people bringing the eats and looking after the coffee.” In spite of such problems, though, as a small-city organization the QHA differed from those situated in larger centres, which were more frequently sex-segregated in response to the different priorities of gay men and lesbians of the time: gay men were often more likely to organize against the policing of gay male sexuality, while lesbian feminists would prioritize child custody issues and male sexism, including that of the gay men. In Kingston, the small size of the community encouraged QHA members to overlook differences of class, gender and sexuality in order to foster supportive bonds based on shared sexual difference. As Dan remarks, “we in Kingston felt…that we can’t really afford to have two separate movements, two separate communities, you really need each other”.

The desire for a gender-integrated group came most directly under fire when the QHA organized a national conference in the spring of 1976 on women’s participation in the Gay Liberation Movement. Although the QHA welcomed both men and women to attend, just before the conference the QHA received a letter from the Gay Alliance Toward Equality, whose membership consisted mainly of gay men, stating that GATE felt that “the matters considered by the conference are matters which only gay women themselves can discuss and resolve in an atmosphere in which predominantly male organizations like GATE are not participants”. At the opening plenary, participating members of Wages Due Lesbians from Toronto decided to take matters into their own hands and made a motion to split the conference. With support from all male participants, the women decided to meet separately and only reconvened with the men on the Sunday afternoon for a final report. Even though the conference had taken an unexpected turn, organizers still considered it a success since forty women and fifty men attended it and these participants did end up discussing issues relevant to women’s involvement in the movement.

Because the group was based at the university, the QHA also in some ways perpetuated the town/gown split. Although officially open to gays and lesbians outside of Queen’s, in its early days the QHA did not do any formal outreach into the wider community, limiting its publicity to the Queen’s Journal and relying on word of mouth to reach Kingston gays. By the mid-seventies, the group had become more open to Kingston residents, but priorities still differed because, as Harvey remembers, Kingston members “wanted to make a gay life in Kingston” and they saw no point in going to Toronto to meet people because “that’s not where their life was”. Queen’s students, on the other hand, “only saw Kingston as a place to go to school” and would go to Ottawa, Montreal and Toronto to meet other queer people.

By 1974, The QHA had submitted a copy of their constitution in order to be recognized as an AMS organization. By fall of 1975, the QHA had secured funding of $250 and established committees to handle publicity, finances, education, a small resource library and the Rap Line. The QHA began to do more community outreach, speaking at numerous high schools, St. Lawrence College, the medium-security penitentiary, and psychology and medicine classes at Queen’s. In 1976 the QHA published its first newsletter, and by 1977, the QHA was holding dances, licensed events in the basement of the Queen’s Law School, every few months, and there were often up to 150 people there, at least half of them women and three quarters of them from Kingston and other towns, including Peterborough, Picton, Brockville, and Smith Falls.

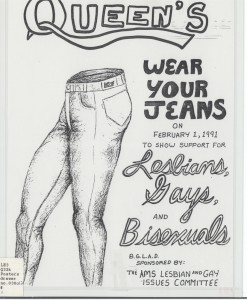

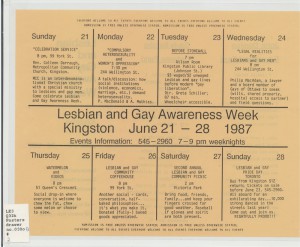

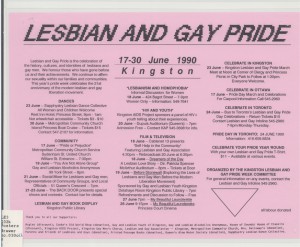

Although the QHA was at times very vibrant, between 1973 and 1980 the organization did sometimes stumble along, its vitality frequently dependent on the presence of a few charismatic leaders. In its time, the organization has changed names as well as leaders, being known as the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Association in the 1990s until 1998, when it acquired its current name of The Education on Queer Issues Project (EQuIP). As EQuIP, the group was responsible for organizing the first Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Awareness/Pride Week on Queen’s campus in March 2007, and EQuIP continues to invite speakers and organize events of various kinds from its headquarters in the Grey House.

Meanwhile, other queer groups have arisen in Kingston to cater to various parts of the city’s diverse queer community. Queer Students on Campus (QSOC) services the St. Lawrence student community, Womyn Kingston provides a listing of women’s services for the community at large, the Queer Forum and the “Out in Kingston” website provide information about queer events in the city, Kingston Pride organizes the annual Pride parade and Pride month events in the city, and reelout holds an annual queer film and video festival, to name only a few of these organizations and groups.