Street Address: 76 Stuart Street, Watkins Wing – The Kingston General Hospital

We are currently standing outside the Watkins Wing of the Kingston General Hospital which is where the first meeting of Parliament in the Province of Canada was held on the 14th of June 1841.[1] It also the place where some “fowl politics” happened in the early 20th century. Jeremy G. Gordon (2020) coined the term “fowl politics” to describe how chickens, through their sounds and presence in urban spaces, challenge anthropocentric ideas of the city as a human space.[2] Chickens and roosters were ubiquitous in Kingston 200 years ago. Their clucking and cawing would have been a common feature of the city soundscape, as would the subtle taps and scurries of their feet as they went from yard to yard searching for food, their alarm calls when evading predators like weasels, humans or hawks, and of course the roosters’ sunrise salutations. But, in the early 20th century, chickens’ and roosters’ urban presence and sounds were increasingly challenged by ideas of the city as a modern and human space.

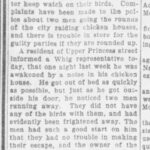

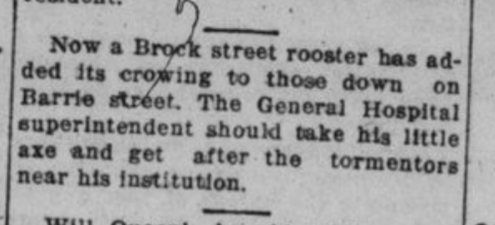

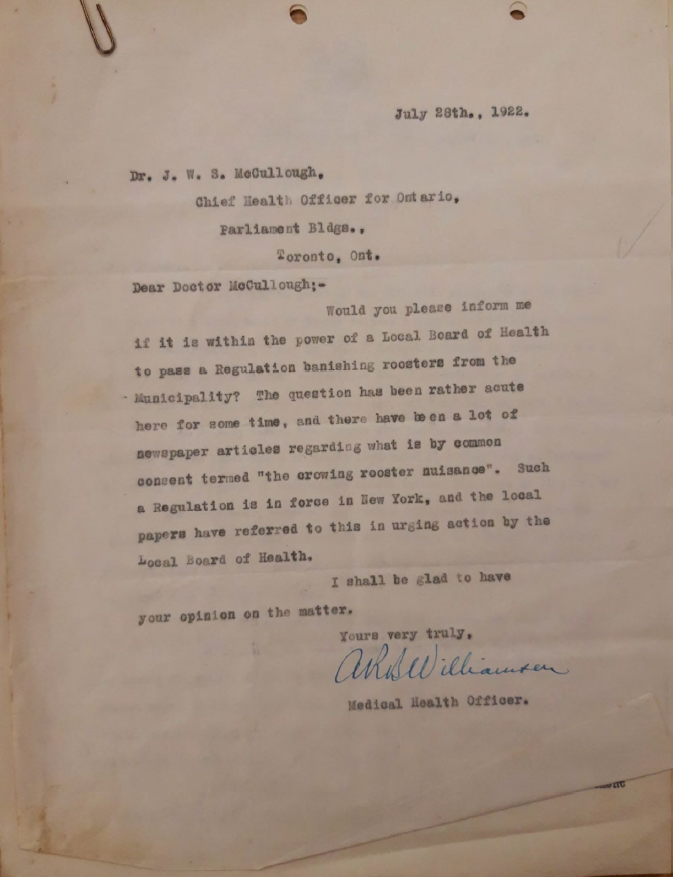

In 1922, the Kingston’s Board of Health found the cawing of roosters “offensive” and the Acting Chief Officer of Health for the City at the time (Dr. Williamson) was determined to find a way to ban the animals from the city. He wrote to the provincial authorities[3] to see if there was any precedent for such a move and on the 1st of August 1922, he received a response.[4] The Chief Health Officer of Ontario (Dr. J.W.S McCullough) stated that Toronto had had similar concerns and came up empty handed, finally saying: “I do not think you can legally banish these birds from the municipality.” He did, however, provide a potential loophole stating that an ordinance that requires the stoppage of unnecessary noise between the hours of 10p.m. and 7a.m. might provide enough of a “bluff” to require owners to “get rid of” their birds. These sentiments seem to have gained traction because only a few days later it was reported in the Daily British Whig that the Sanitary Inspector was telling people to remove their birds or face prosecution for noise disturbances.[5] Roosters were blamed for “keeping nervous patients awake for nights” at the Hospital, becoming what the author termed a “menace to health”. It appears that the bluff was working because whenever owners were told to “stop the birds crowing” they “obeyed in every instance”.

Some attempted to quieten their birds by muzzling them or putting them in cramped boxes that prevented them from elongating their necks, but most, likely, opted for “cutting their throats”, a strategy endorsed by “The Man on Watch” who in October 1922 stated in the Daily British Whig that The General Hospital superintendent “should take his little axe and get after the tormentors near his institution.”[6]

While this was all done under the guise of managing the health impacts of noise, when you consider that a rooster’s caw is in a similar decibel range to that of a dog’s bark or that “noises such as those made by boats whistling in the harbor”[7] were not targeted in the law, it seems that something other than noise was at issue. Perhaps it was the early morning nature of their calls, or because roosters were not thought of as pets, or maybe it was because the sounds roosters made did not fit with emerging ideas of what a modern city should be like. Either way, roosters, with their proud plumage and calls, remain prohibited in many cities, including Kingston.

While roosters’ calls might be one of the most emblematic sounds humans associate with chickens, scientists have long been interested in chickens for the diversity of their sounds. In the 1980s Nicholas E Collias (1987) started exploring how chicken sounds were tied to cognition and since then, at least 24 different types of chicken sounds, with distinct social and community meanings have been identified.[8] These include a low murmuring or even purring when chickens are content, alarm calls, egg-laying songs, growls, and roll calls.[9] Not only are chickens very vocal but they are adept at hearing both high and low frequencies. Researchers think chickens’ complex sound repertoire is indicative of their sophisticated cognitive abilities and have found them to be highly intelligent, socially complex animals.[10]

With chickens being the most consumed land animal in the world and Ontario responsible for over a third of Canada’s 747,000 annually-slaughtered chickens, most people in Kingston only encounter silenced chickens in supermarkets.[11] That said, there are some clucking chickens[12] in the city too. Kingston’s by-laws changed in 2011 to once again allow people to keep up to six hens in their back yards.[13] Roosters, though, remain prohibited (and are frequently killed or offloaded onto rescue organizations).[14] The “fowl politics” of Kingston’s returning chickens is still unfolding.

Notes and Credits:

Images:

- 1922-05-06, “The Rooster.” The Daily British Whig. Page 12.

- 1922-06-21, “Roosters in Cities.” The Daily Standard. Page 4.

- 1922-06-22, “Letter to the Editor: Noisy Roosters.” The Daily Standard. Page 13.

- 1922-06-30, “Object to the Roosters.” The Kingston Whig-Standard. Page 5.

- 1922-07-27, “Letter to the Editor: Noisy Roosters.” The Daily Standard. Page 4.

- 1922-07-28, Queen’s University Archives, Board of Health Correspondence, Box 245, Letter from Kingston’s Medical Health Officer to Dr. J.W.S. McCullough.

- 1922-08-01, Queen’s University Archives, Board of Health Correspondence, Box 245, Letter from the Acting Chief Officer of Health.

- 1922-08-03, Queen’s University Archives, Board of Health Correspondence, Box 245, Follow up letter from the Acting Chief Officer of Health.

- 1922-08-03, “Noisy Roosters.” The Daily Standard. Page 3. Available from Newspapers.com:

- 1922-08-10, “Roosters Must not cause an annoyance.” The Daily British Whig. Page 7.

- 1922-10-07, “The Man on the Watch.” The Daily British Whig. Page 13.

Extras:

- Veganism, Archives and Animals: Geographies of a Multispecies World, by Catherine Oliver

- Chicken, book by Annie Potts

- Personalities on the Plate: The Lives and Minds of the Animals we Eat, by Barbara J. King

- For the Birds:From Exploitation to Liberation, by Karen Davis

- Prisoned Chickens: Poisoned Eggs, by Karen Davis

- Thinking chickens: A review of cognition, emotion, and behaviour in the domestic chicken an academic article by Lori Marino.

- United Poultry Concerns, organisation dedicated to the compassionate treatment of domestic fowl

- Bird Flu: Domestic Chicken Keepers could be putting themselves – and others – at risk a Conversation piece by Catherine Oliver.

- Episode with pattricejones talking about chickens as survivors, on The Animal Turn Podcast.

- Episode with Catherine Oliver talking about Urban Metabolism focused on chickens, on The Animal Turn Podcast.

- Animals and Sound, season 4 of the Animal Turn Podcast

Footnotes:

- [1] “Canada’s first Parliamentary building” Accessed from Kingston’s Health Sciences Center. Thank you also to Heather Homes for making the political connection here.

- [2] Gordon, J.G., 2020. A fowl politics of urban dwelling. Or, Ybor City’s republic of noise. Journal of Urban Affairs, 44(2):194-200.

- [3] See his letter to Dr. J.W.S. McCullough, the Chief Health Officer for Ontario dated 28 July 1922. This can be found in the Board of Health Correspondence, Box 245, Queen’s University Archives.

- [4] The response came from the Acting Chief Officer of Health and can also be found in the Board of Health Correspondence, box 245, Queen’s University Archives. He sent an additional letter the very next day to say that he was mistaken in saying that the Toronto Board of Health has an “ordinance” covering the matter but that the problem of unnecessary noises is covered in the Public Health Act and municipalities have “ample power” to “see that these nuisances are abated.”

- [5] 10 August 1922, “Roosters Must not cause an annoyance.” The Daily British Whig. Page 7. Available from Newspapers.com.

- [6] 7 October 1922, “The Man on the Watch.” The Daily British Whig. Page 13. Available from Digital Kingston.

- [7] 10 August 1922, “Roosters Must not cause an annoyance.” The Daily British Whig. Page 7. Available from Newspapers.com.

- [8] Collias, N.E., 1987. The vocal repertoire of the red junglefowl: A spectrographic classification and the code of communication. The Condor, 89(3):510-524. See also Collias, N.E. and Collias, E.C., 1967. A field study of the red jungle fowl in North-Central India. The Condor, 69(4):360-387; and Collias, N. and Joos, M., 1953. The Spectrographic Analysis of Sound Signals of the Domestic Fowl. Behaviour, 5(3):175-188.

- [9] See Lesley, C., 2020. “11 Common Chicken Sounds: How to Speak Chicken” for a brief summary of these sounds. Available from Chickens and More. Also find a summary on The Happy Chicken Coop.

- [10] Marino, L., 2017. Thinking chickens: A review of cognition, emotion, and behaviour in the domestic chicken. Animal Cognition, 20(2): 127-147.

- [11] Find the poultry and egg statistics for Canada here, May 2020 and annual 2019. From Statistics Canada. Also read this article by Labchuk, C., 2020. Canada slaughtered 834 Million Animals in 2019. Available on Animal Justice.

- [12] Schiesmann, P., 2013. Backyard coop project not ruffling feathers. Available from The Whig Standard. Balogh, M., 2020. ‘Chickens are the new toilet paper’: People flock to backyard chickens, gardens amidst pandemic. Available from the Whig Standard.

- [13] City of Kingston, Animal and Pet Regulations.

- [14] Ferguson, E., 2017. Rooster, neighbour ruffle feathers. Available from The Whig Standard/